At the 2022 COP27 climate change conference, Japan nabbed the satirical Fossil of the Day award for its investments in dirty energy. This wasn’t the first time the country had received the accolade, and it was further proof that the world’s fifth-highest CO2 emitter has much room for improvement if it wants to be environmentally sustainable.

Japan is often called a country of convenience, a statement typically at odds with a sustainable lifestyle. But don’t let that deter you. With some planning, it’s possible to be more environmentally friendly in Japan. And while policy changes will ultimately lead the way, individuals can make a difference, too.

Here are 10 ways to live more sustainably in Japan:

- 1. Choose a green energy provider

- 2. Use greener transport options

- 3. Compost at home to grow sustainable produce

- 4. Reduce plastic waste

- 5. Shop locally and sustainably

- 6. Download the right green and circular economy apps

- 7. Go paperless with online banking

- 8. Control your water usage

- 9. Replace old appliances and conserve energy

- 10. Recycle, recycle, recycle

- Useful resources

1. Choose a green energy provider

Japan’s current renewable energy (再生可能エネルギー) target is 36–38% of the overall mix by 2030. This remains lower than the ambitious targets of other developed nations, but it’s representative of the government’s increasingly optimistic climate rhetoric.

To that end, former Prime Minister Fumio Kishida (岸田 文雄) has designated ¥150 trillion (US$1.15 trillion) for financing the renewables sector over the next decade and has introduced policies to increase the potential of solar (太陽光) and offshore wind (洋上風力) energy.

As the government focuses more on combatting climate change (気候変動), it’s becoming easier for consumers to make sustainable energy choices in Japan. There are currently 723 registered energy providers offering competitive deals to compete in the congested market:

- Looop (ループ): a one-stop-service utility provider that reinforced its commitment to renewable energy in 2022. It recently partnered with ultrathin-film solar cell company Heliatek to install organic solar photovoltaics (i.e., conversion of light into electricity using semiconducting materials) throughout Japan.

- Minna Denryoku (みんな電力) (in Japanese): has a power procurement policy whereby it will only supply power from environmentally sustainable companies

- Green People’s Power (グリーン ピープルズ パワー) (in Japanese): aiming for 100 % renewable energy delivery to Japanese residents

- Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO) (東京電力): Japan’s largest energy provider, now offering carbon-free electricity through its Aqua and Sunlight plans

For further information or updates, check out the Renewable Energy Institute (自然エネルギー財団), a nonprofit organization (NPO) combining the brightest minds in Japan’s sustainability sector.

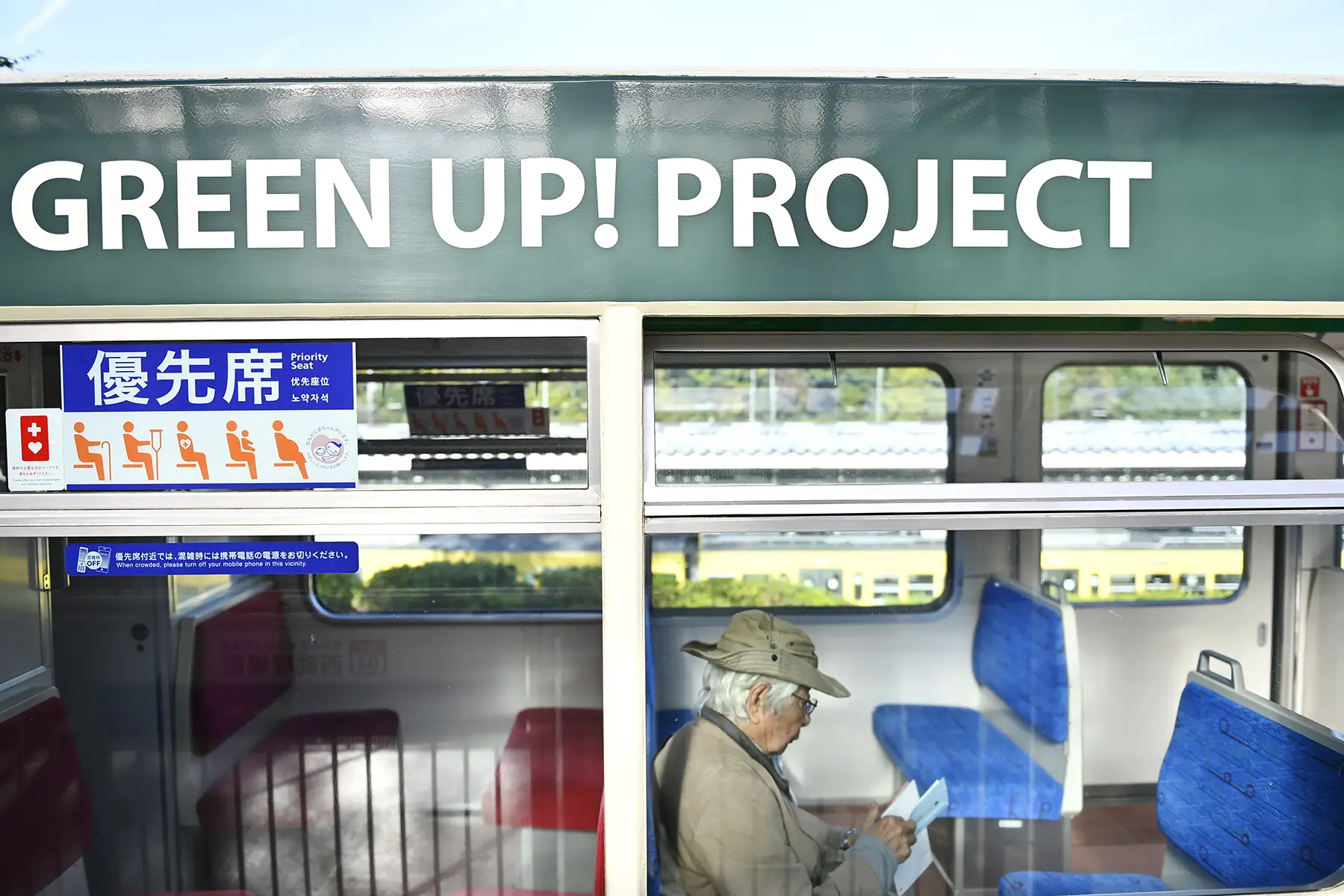

2. Use greener transport options

Japan’s hyper-efficient transport system means travel in the major cities is relatively sustainable. If you live in Tokyo (東京), Osaka (大阪), Fukuoka (福岡), or Nagoya (名古屋), for example, there’s little need to drive a car because the public transport systems are widespread and reliable.

Case in point: the Tokyo Metropolitan Area ranked seventh among transit systems globally, according to the 2022 Urban Mobility Readiness Index, despite its population of more than 37 million people spread over 5,000 square miles (13,000 square kilometers).

The bullet train, also known as the Shinkansen (新幹線), sends travelers to all corners of Japan for cross-country travel. So there’s little need to fly unless you want to cut costs. The price of a Shinkansen from Tokyo to Osaka is twice as much as a flight with budget air carriers, but it emits 8.33% of the amount of CO2.

You can also live more sustainably in Japan with labor-intensive modes of travel. Tokyo’s flat topography, abundant sidewalks, and diverse neighborhoods make walking and cycling great methods of exploration.

These can also be convenient ways to commute, as Japanese city neighborhoods often have great facilities, such as supermarkets, convenience stores, parks, and train stations.

Bicyle-sharing

Bike-sharing schemes have also grown in popularity. The Docomo bike share service (ドコモ・バイクシェア) connects e-bike (電動自転車) stations spread across:

- Tokyo Metropolitan Area

- Sapporo (札幌)

- Kanazawa (金沢)

- Kobe (神戸)

- Hiroshima (広島)

- Nara (奈良)

- Osaka

- Kagoshima (鹿児島)

- Oita (大分)

The e-bike provider in each host city differs, but they’re all accessible through the Docomo app.

The electric vehicle (EV) (電気自動車) market in Japan is a little behind the curve, however; hybrids (ハイブリッド車) still accounted for almost 99 percent of domestic EV sales in 2021. Therefore, the government has introduced purchasing subsidies to encourage greater uptake, including ¥650,000 (US$5,200) for battery electric vehicles (BEVs) and ¥2,300,000 (US$18,500) for fuel-cell electric vehicles (FEVs).

3. Compost at home to grow sustainable produce

Most Japanese households will separate their trash into various waste and recycling categories. But a lack of clear distinction means food waste sometimes ends up with burnable trash, thus contributing to landfills. If you want to live more sustainably in Japan, consider these compost tips:

- Deposit all fruit and vegetable scraps in a plastic container on your balcony, garden, or veranda. Then mix with water and brown leaves or coffee grounds. After several weeks you can reuse the compost as a soil feeder for growing fresh Japanese crops.

- You can buy compost bins at garden stores, which you’ll find in most residential neighborhoods, or on e-retail sites like Amazon and Rakuten (楽天市場). Some 100-yen shops (100円ショップ) like Daiso or Can Do will also sell suitable containers.

- As Japanese households are traditionally small, there are plenty of community gardens and allotments where you can use compost. Here’s a list of gardens with staff to help members use the facilities.

- If you’re interested in urban farming, check out Tokyo-based Business Grow, which runs workshops on growing crops in Japanese cities

4. Reduce plastic waste

Japan is notorious for plastic use. It produces more than 20 billion plastic bottles annually, a full 14% of which aren’t recycled. In comparison, the average Japanese person uses 450 plastic bags a year, with many ending up in incineration plants or as pollution in the world’s oceans.

So, one of the easiest ways to be more sustainable in Japan is to cut down on the amount of plastic you use:

- Instead of buying drinks – in single-use plastic bottles – at one of Japan’s four million vending machines, bring a flask or reusable water bottle when you leave the house. Many parks have drinking water fountains for public use, or you can download the mymizu app to find free water refill stations throughout the country.

- Bring a reusable container and chopsticks (or a knife and fork) in your bag to avoid throwaway packaging when ordering takeout. A travel coffee cup is also a good idea.

- Take your own bag when buying groceries. You may want to memorize the phrase, fukuro wa iri-masen (I don’t need a bag), as many shop tellers will still reach for the plastic bags before asking if you require any.

- Try to shop at markets and greengrocers, as supermarkets usually package their fresh produce in plastic

- Use online resources. The Sustainable Living Tokyo Community is a great source of waste-mitigation information.

5. Shop locally and sustainably

Shopping at local greengrocers or farmers’ markets is a great way to live sustainably in Japan. As an island nation, the country has spent significant portions of its history in isolation from the rest of the world, allowing native crops to flourish in abundance.

These crops bloom across 72 micro seasons and are at their most delicious – and affordable – when in season. Buying in-season produce negates the need to purchase imported foods and, in turn, reduces the carbon footprint of your shopping trips.

Examples of seasonal Japanese crops:

- Winter: green onion, Chinese cabbage, radish, lotus root, strawberries, mikan oranges

- Spring: asparagus, eggplant, wood-ear mushrooms, shiitake mushrooms, snow peas, mango, melon

- Summer: edamame, pumpkin, cucumber, perilla, bitter gourd, figs, yuzu, plums

- Fall: matsutake mushrooms, sweet potato, chestnut, persimmon, grapes, pears

There are almost 3,000 year-round farmers’ markets with annual sales of at least ¥100 million (US$753,000) in Japan, and many other smaller or weekly markets that pop up across the major cities. The Aoyama Farmers’ Market, one of the most popular in Tokyo, also publicizes news on its website highlighting sustainable food venues across Japan.

6. Download the right green and circular economy apps

As in most countries, you’ll find many useful apps in Japan for public transport, language learning, mobile banking, checking the weather, or for finding the best cuisine.

Fortunately, you can also download apps for sustainable living in Japan:

- Mymizu: an app for combatting plastic waste, plus highlights free water refill stations nationwide

- Mercari (メルカリ): a popular marketplace app allowing you to buy and sell second-hand goods

- Jimoty (ジモティー): a great place to find (often free) used items

- Mamoru: means “to protect”, a sustainable living app that lists zero-waste businesses, ethical retailers, sustainable produce markets, and second-hand stores

- Tabete: a circular economy app that allows users to pick up excess food from nearby restaurants, cafes, and bakeries, so it does not go to waste

7. Go paperless with online banking

Japan’s high-tech image precedes it, but it has primarily remained a paper and ink economy in the digital era. You’ll find many administrative processes still require signing physical forms and appearing in person, including registering a new address, opening a bank account, paying utility bills, or extending your work visa.

Most utilities providers will send the bills via post to your home, which you can pay via cash (cards not accepted) at a local convenience store. You can also transfer the money online or set up an automatic withdrawal each month. The latter will require filling out an application form that can take up to a month to process.

Mobile banking apps have improved significantly in the past few years, making day-to-day life in Japan more sustainable.

Also, note that many independent Japanese businesses still only accept cash. Those that have digitalized will usually accept debit and credit cards, as well as e-cash stored on rechargeable transport passes and mobile e-payment methods, like PayPay and Line Pay.

8. Control your water usage

Japan receives ample rainfall each year, but due to its mountainous landscape, water flows quickly to the sea. Combined with a high population density, particularly on the east coast, this means the amount of usable water per person – 119,000 feet (3,373 cubic meters) – is half the global average.

When you conserve water, you live more sustainably, as it can help mitigate water shortages, such as the crisis of 1994, which affected almost all of Japan. Adapting how you use water-based appliances is a good start:

- Japanese toilets: use the small flush (indicated by the 小 kanji), and don’t overuse the bidet options (usually represented by self-explanatory pictographs)

- Baths: Japanese tradition dictates that people reuse bathwater for multiple members of the household, much like sharing water in an hot spring (温泉). Domestic bathrooms usually have a separate shower so you can clean yourself before entering the bath.

- Showers and sinks: purchase and install water-saver showerheads or low-flow taps. For example, the Amane Heavenly Rain showerhead can reduce water consumption by up to 35%.

Municipalities control the water supply in each region, so if you have further queries on costs or conservation, it’s best to get in touch with your local provider. In Tokyo, this is the Bureau of Waterworks (東京都水道局).

9. Replace old appliances and conserve energy

Due to increased CO2 emissions in the residential sector, the government introduced an Energy Efficiency Labeling Scheme. If you want to be more sustainable, choose air conditioners, refrigerators, TVs, and other appliances that have a five-star rating.

You’ll find energy-saving appliances from the nation’s most renowned manufacturers at major electronics chains: Yodobashi Camera (ヨドバシカメラ), Yamada Denki (ヤマダデンキ), Bic Camera (ビックカメラ) (all in Japanese).

Check websites for seasonal offers and rainy-day deals.

Purchasing a kotatsu (こたつ) is another energy-saving solution. These low tables have built-in heat sources (usually electrical) and are covered by a thick futon or blanket. Studies by the Tokyo Metropolitan Government suggest using a kotatsu could reduce your CO2 output by 24kg per year. In comparison, an electric carpet at medium heat could slash your output by 91kg.

If you’re buying new appliances, you’ll want to get rid of those old ones. Try selling used machines to second-hand electronics stores – Hard-Off has locations in all 47 prefectures of Japan – or bring them to an appliance store. Many major chains are obligated to accept used items. You can also upcycle appliances you no longer need through Facebook at Tokyo Sayonara Sales and Tokyo Garage Sales.

10. Recycle, recycle, recycle

Waste management in Japan is complex because each municipality sets its own rules for disposal and recycling; when registering your address, your local ward office will provide you with this information (often in Japanese).

Typically, Japan has few public trash cans because residents are expected to sort their trash at home. Most apartment buildings and complexes will have waste and recycling units. In some areas, like zero-waste town Kamikatsu (ゼロ ・ ウェイストタウン上勝), residents will separate their trash into 13 categories and 45 subcategories. In contrast, people in central Tokyo may have only three or four broader waste categories.

Some of the most common categories include:

- Burnable (燃えるゴミ): anything that can be incinerated, including some plastic waste and cardboard

- Non-burnable (燃えないゴミ): broken glass and ceramics, batteries, damaged electronics, and lighters

- Recyclable (資源ゴミ): plastic and glass bottles, cans, cardboard, and other plastics

- PET bottles (ペットボトル): 100% recyclable plastic bottles (caps often need to be removed)

- Oversized items (粗大ゴミ): usually collected upon appointment by the sanitation authorities

Clothes are among the easiest items to upcycle or recycle, as many fashion brands repurpose unwanted clothes and accessories, such as:

- Casafline: sells masks made from upcycled materials

- Nozomi Project: jewelry made from broken ceramics

- Plasticity (in Japanese): creates bags from discarded umbrellas

- Relier81 (in Japanese): makes women’s shoes from second-hand kimonos

Useful resources

- Tokyo Expat Network – an English-language international forum for all questions relating to living in Japan

- Kiko Network – a valuable source of independent information for climate-conscious residents of Japan

- Zenbird – an online magazine focusing on sustainable living in Japan