When moving to a new country, it’s essential to know your human and civil rights as a resident. In Italy, these include fundamental liberties like freedom of speech and social welfare rights, such as parental leave and public healthcare. Although Italy scores high globally regarding human rights, there is room for improvement in protecting vulnerable groups.

Read on for more about human rights in Italy looking closer at these sections:

- Overview of human rights in Italy

- Italian civil rights

- Political rights in Italy

- Italian social and cultural rights

- Italian workers’ rights

- Women’s rights in Italy

- Italian disability rights

- LGBTQIA+ rights in Italy

- Anti-racism and anti-discrimination legislation

- Migrant and refugee rights in Italy

- What to do if your rights are abused or restricted

- Human rights organizations

- Useful resources

Ground News

Get every side of the story with Ground News, the biggest source for breaking news around the world. This news aggregator lets you compare reporting on the same stories. Use data-driven media bias ratings to uncover political leanings and get the full picture. Stay informed on stories that matter with Ground News.

Overview of human rights in Italy

Italian human rights are based on the 1948 Constitution and the European Union (EU) and United Nations (UN) Universal Declaration of Human Rights principles. Italy is a member of both. These postwar developments followed the period of fascist rule in Italy in which a totalitarian system limited its people’s civil, political, and social rights.

While those living in Italy today enjoy a wide range of rights, inequalities remain in practice, and rights abuses still occur.

Italy’s internal rights-based system

Italy’s 1948 Constitution grants civil, ethical, social, economic, and political rights to those living there. The Constitution also details how the three branches of the state – parliament, government, and judiciary – organize to protect the rights-based system and prevent the development of an authoritarian regime.

The Ministry of Justice (Ministero della Giustizia) is responsible for human rights legislation in Italy. Although the Italian legal system guarantees all fundamental rights, no independent institutions protect human rights or hold the state accountable. Ad hoc parliamentary commissions or commissioners sometimes deal with rights-related issues. Italy’s lack of an independent national human rights agency has drawn criticism and suggestions to establish an institution according to UN principles.

Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch (HRW) highlight where the Italian government denied or abused human rights. These include restrictions on access to abortion and failure to guarantee the rights of refugees and migrants.

Italy and international human rights

Italy has signed numerous international human rights conventions, including the following UN treaties:

- International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights

- Convention on the Elimination of all forms of Discrimination Against Women

- International Convention on the Elimination – all forms of Racial Discrimination

- Convention Against Torture

The country is also signatory to the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) and the Office of the High Commissioner on Human Rights (OHCHR), which advances these principles within EU member states.

Italy ranks 26th out of 165 countries on the 2021 Human Freedom Index (HFI). It scores highest on personal relationships and freedom of movement but lower in taxation and legal rights.

Italian civil rights

Italy’s Constitution grants many types of civil rights, including:

- Freedom of religion

- Freedom of home life

- Protection of civil liberty

- Freedom of movement within the country and abroad

- Freedom of assembly and protest

- Right to a fair trial

- Freedom of speech and thought

- Freedom of the press

In terms of civilian privacy, the government recently restricted facial recognition in video surveillance. The Italian data protection authority (Garante per la Protezione dei Date Personali) also ensures compliance with the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) laws. Despite these regulations, Italy’s internet freedom score was 76 out of 100 in 2021, with significant shortcomings in protecting internet users from corporate and government monitoring.

A 2021 Amnesty International report flagged evidence of torture and ill-treatment in Italian prisons and police custody.

The Freedom House report also marked Italy down slightly in some civil liberties areas for problems such as:

- Delays in legal proceedings – Italy has one of the lowest number of judges per capita in the EU

- Regional inequalities – organized crime affects property and business rights in some parts of the country

HRW noted that marginalized groups struggled to obtain Italy’s COVID-19 green pass from 2020 to 2022, which residents needed to access most public spaces. This seriously restricted the freedom of movement for migrants and homeless people.

Freedom of speech in Italy

Italians enjoy freedom of speech. However, things are slightly more problematic regarding freedom of the press. One of the problems noted by HFI is journalist self-censorship due to fear of repercussions. As a result, Italy has fallen to 58th globally on the Reporters Without Borders Press Freedom Index (2022). Although there is a wide range of media publications in the country, press freedom is at risk due to organized crime and political extremism. There were 163 recorded acts of intimidation against Italian journalists in 2020.

Italy has had a strong culture of civil society participation over the last 30 years, with citizens readily campaigning for social change and engaging in protests. However, the recently elected Italian government has passed a so-called anti-rave law restricting gatherings of 50 or more in public places. While the government defends this as an act of protecting public order, critics have called it a breach of the Italian Constitution and the ECHR and UN treaties.

Right to a fair trial

Although it generally meets international standards, Italy’s legal system experiences problems such as inefficiency, corruption, and the influence of organized crime. The HFI scores Italy 6.5 for its overall legal system and 6.6 for the rule of law. Problems noted include the courts’ impartiality and the system’s level of integrity.

If arrested in Italy, authorities can only detain you without charge for a maximum of 24 hours. They can remand you in provisional custody without trial for up to three months for minor offenses. This increases to up to 12 months for serious crimes (or 24 months in extreme cases).

Political rights in Italy

Italy is a constitutional democracy where all citizens aged 18 and above can vote in national elections. EU citizens can go to the polls in European and local elections in Italy as long as they register. The same goes for Italian citizens living abroad who can vote by mail if registered. Prisoners and non-EU residents cannot vote in Italian elections.

People can join and form political groups and parties that operate within the law. Citizens aged 25 and older can also run for parliament in Italy.

The Italian Constitution contains provisions for direct democracy, so citizens can propose legislation if they draw up a bill supported by at least 50,000 voters. National referendums and citizens’ initiatives can occur if requested by at least 500,000 voters or five regional councils.

Italy ranks 46th for political rights on the FHI scoring 36 out of 40. It lost points for transparency, corruption, migrant voting rights, and the influence of organized crime.

Italian social and cultural rights

The Italian Constitution protects the social and cultural well-being of its residents and citizens, including:

- Family life and children’s education

- Healthcare

- Freedom of arts and sciences

- Freedom of religion

- Protection of linguistic minorities

- Welfare support for those unable to work

All residents living in Italy for more than three months have access to public healthcare. However, in some cases residents have to pay an annual fee for public service, for example, if you are a student or unemployed (disoccupati).

Housing laws guarantee tenants’ rights in the rental sector, although social housing is usually restricted to citizens and those with long-term residence permits. However, due to discrimination and prejudice, certain groups, such as the members of the Roma community, often have trouble finding housing in Italy.

Education is free for children of all legal Italian residents. Social security and welfare benefits are available, but many are contribution-based.

The Italian Constitution prohibits racial and religious discrimination. Italy scores highly on the FHI report for freedom of cultural expression and spiritual practice. It is also a member of the European Parliament Intergroup for Freedom of Religion or Belief and Religious Tolerance (FoRB&RT). However, minority religions and ideas are often not treated equally. For example, Islam is the biggest non-Christian religion in Italy but historically lacks the same formal recognition by the state.

Italian workers’ rights

Every Italian citizen has the right to work or become self-employed. This right extends to citizens from the EU and European Free Trade Association (EFTA – Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway, and Switzerland) due to freedom of movement laws. Non-EU/EFTA citizens need a work visa in Italy. It is also illegal to employ children under the age of 15.

Italian labor law is a mix of national and EU-wide regulations. Employers can only dismiss contract employees with good reason or within the required notice period. Work hours should not exceed 48 hours; anything beyond 40 hours is overtime. Workers are entitled to paid holiday, maternity/paternity leave, and sick leave, depending on their contract and hours worked. Italy has no minimum wage, but collective bargaining agreements protect about half of all workers.

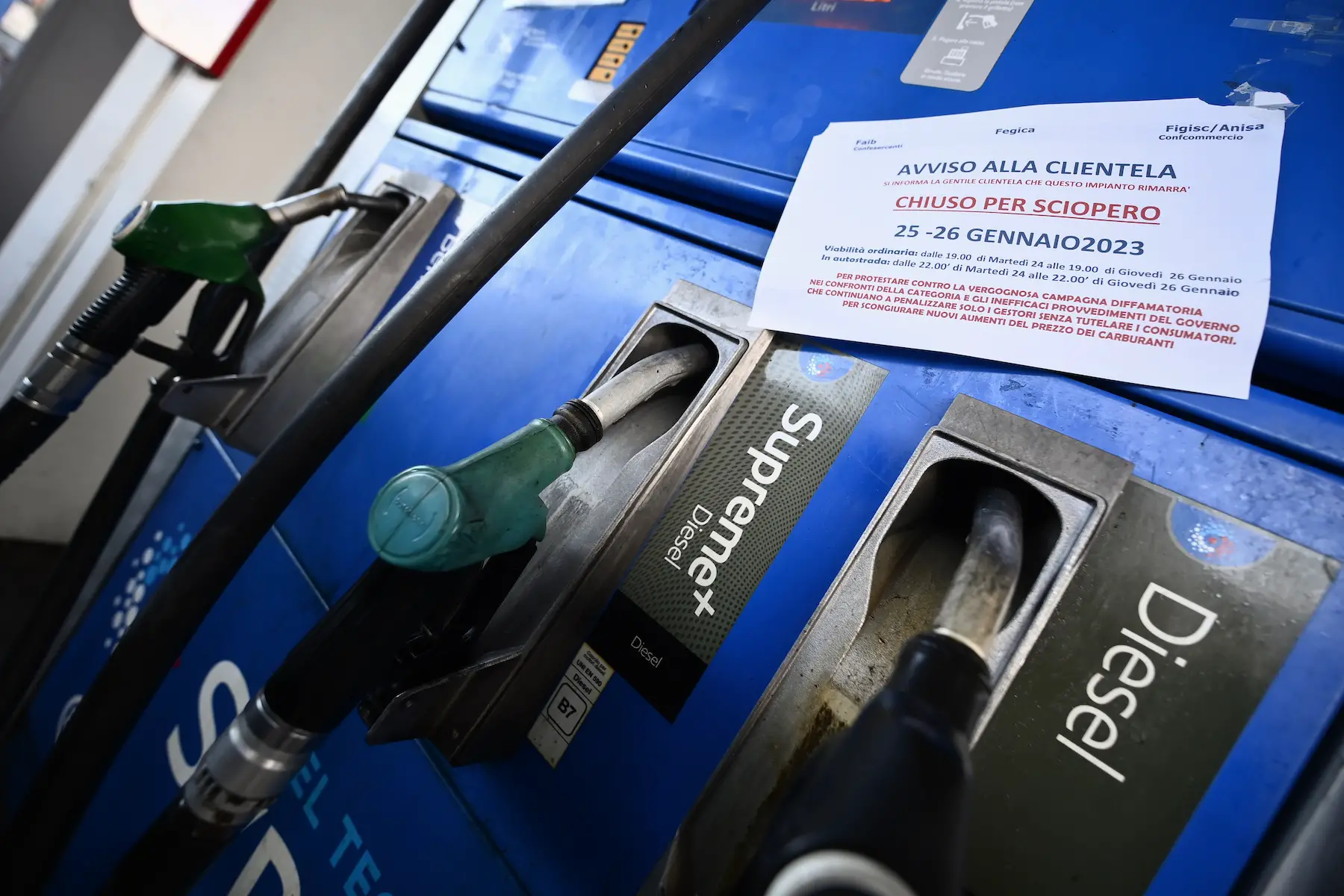

Trade unions are commonplace, with over a third (35%) of all workers belonging to one. All workers in Italy have the right to join a trade union and participate in strikes. However, specific industries, like healthcare and transportation, have some strike restrictions.

Discrimination based on sex, race, religion, language, or political opinion is illegal in Italian workplaces. However, Amnesty International reported that some healthcare workers were unfairly dismissed or restricted from union activities for raising concerns about working conditions during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Women’s rights in Italy

Italy outlawed discrimination against women in its Constitution and signed the UN Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW). Certain laws around divorce and abortion further secure women’s rights. Furthermore, the Italian government has engaged in international campaigns to end practices such as female genital mutilation (FGM) and forced marriage.

However, gender inequality, sexual violence, harassment, and barriers to access still exist in Italy. One of the biggest current problems is restricted access to abortion due to many doctors and women’s healthcare providers refusing to perform it.

In a 2018 study, almost 50% of Italian women reported having experienced sexual harassment. As was the case in many countries, domestic violence increased during the COVID-19 lockdown periods. A devastating 102 women were killed; 70 by their partners or ex-partners (2021).

Many areas of Italian society remain male-dominated, and gender role stereotypes prevail. Despite introducing gender quotas for political roles, the Italian Parliament has two men for every woman and ranks 56th globally, according to the Inter-parliamentary Union (IPU). Italy also ranks 63rd on the 2022 Global Gender Gap Report by the World Economic Forum (WEF) and 14th in the EU on the 2022 Gender Equality Index.

Italian disability rights

Italy signed the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, and Article 3 of its 1948 Constitution states that all citizens are equal regardless of personal and social conditions. The country has passed several laws regarding inclusive education (Bisogni Educativi Speciali), such as the right for children with disabilities to be educated in mainstream schools (circa 1971). Italy joined the European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education in 1996.

Other laws covering disability rights include:

- Ensuring that public buildings meet EU accessibility standards

- Employment laws to promote workplace inclusion – for example, quota systems for larger companies

With the 6th lowest gap in employment rate, Italy scores well in economic inclusion of people with disabilities, according to EU statistics. It also has the 2nd smallest gap for risk of poverty or social exclusion. However, inequalities still exist. For example, the recent lack of support for one family was ruled a UN human rights violation. Furthermore, current government legislation does not protect those with disabilities against hate crimes.

LGBTQIA+ rights in Italy

Workplace discrimination against gay and transgender people is illegal in Italy, and citizens have been able to change their gender since 1983 officially. There are no restrictions on those identifying as LGBTQIA+ donating blood, and the community does not regularly experience censorship. However, while civil unions have been allowed since 2016, gay marriage is still not legal.

Italy falls behind other EU nations in several critical areas of LGBTQIA+ rights. According to the 2022 ILGA-Europe Rainbow Map, Italy ranks 33rd out of 49 European countries for LGBTQIA+ rights and freedoms. Although there are reasonable legal protections, fundamental problems include inequality, discrimination, and hate crimes. Unfortunately, the Italian Senate recently blocked a bill recognizing hate crimes against the LGBTQIA+ community.

Critically, those who identify as LGBTQIA+ don’t have equal adoption rights in Italy, and Italian birth certificates cannot name same-sex parents. Another issue is abuse in public, with 40% of LGBTQ+ individuals in Italy reporting regular discrimination.

Italy ranks 50th globally on the LGBTQIA+ Equality Index with an overall score of 65 out of 100. It scores 75 on the legal index but only 54 on the public opinion index.

Anti-racism and anti-discrimination legislation

The Italian Constitution “recognizes and guarantees the inviolable rights of the person, both as an individual and in the social groups where personality is expressed” (Art. 2). It also states that citizens are “equal before law, without distinction to sex, race, language, religion, political opinion, personal and social conditions.” (Art. 3).

The government has passed several pieces of anti-discrimination legislation since then, including:

- Decree 205/1993 – ethnic, racial, or religious intolerance is punishable by up to three years in jail

- Decree 482/1999 – protection of linguistic minorities, including Albanian, Croatian, French, German, and Greek

- Laws 215/2003 and 216/2003 – criminalizes both direct and indirect discrimination – including harassment – in the public and private sphere

To help fight racism and discrimination, the Italian government set up:

- 2004 – The National Office Against Racial Discrimination (Ufficio Nazionale Antidiscriminazini Razziali – UNAR)

- 2010 – The Observatory for Security Against Acts of Discrimination (Osservatorio per la Sicurezza Contro gli Atti Discriminatori – OSCAD)

Despite anti-discrimination laws, migrant and minority groups still experience violence and harassment in Italy. The Italian police recorded 1,445 hate crimes in 2021, with 80% relating to racism or xenophobia. Anti-Roma racism is rampant in Italy today, and antisemitism appears to be surging.

A 2019 OHCHR investigation into racial hatred and discrimination concluded that the Italian government must take action at the legislative level to tackle these problems. This includes establishing an independent human rights institution within the country’s government.

Migrant and refugee rights in Italy

Italy is home to around 5 million foreign residents, making up 8.8% of the population. Although migrants’ civil rights are generally protected, they lack some political and social rights given to Italian citizens. This is evident in the fact that only EU nationals can vote, and many welfare and social entitlements depend on residency length or contribution amount.

According to EU asylum statistics, 52% of asylum applications are initially refused in Italy compared to the 62% EU average.

Italy’s migration policy has become even more strict since September 2022, with migrants being refused disembarkation after docking. As such, the Council of Europe Commissioner for Human Rights has criticized the country for its poor treatment of migrants arriving by boat from across the Mediterranean Sea.

Asylum-seekers, new arrivals, and those on temporary visas generally have fewer rights than long-term residents and citizens. Italy’s membership in the 1951 Geneva Convention means anyone can claim asylum in the country, but they often have trouble finding work and accommodation. Many live in poor conditions and overcrowded housing with limited recourse unless they gain refugee status.

Amnesty International noted that there were 300,000 migrants without documentation in Italy in 2021, making it difficult to secure their rights. The report detailed several cases of human rights abuse experienced by migrants in the country, including:

- Exploitative work conditions

- Inadequate housing

- Racist attacks

- Illegal expulsions to unsafe countries

- Criminalization of groups assisting new arrivals

The 2022 Human Rights Watch report also documents several individual human rights abuse cases.

What to do if your rights are abused or restricted

If you’ve experienced a violation of your human rights while living in Italy and aren’t sure where to report it, you can use the EU justice e-portal to find out. Once you’ve answered some questions about the situation, you’ll receive the website, email address, and phone number of an agency that can help.

If you are unsatisfied with the response from Italian authorities and want to escalate your report to an international body, you can contact the European Court of Human Rights. There is a strict process to be able to appeal, and you must have exhausted all potential domestic routes to remedy the situation to qualify. If you are not satisfied with the European Court verdict, you can contact the UN Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner.

Human rights organizations

There are a number of social sector organizations that work to promote and support human rights in Italy. These include:

| Organization | Type | Purpose |

| Italian Coalition for Civil Liberties and Rights (Coalizione Italiana Libertà e Diritti Civili – CILD) | Italian organizational network | Connect civil society organizations throughout Italy |

| Italian Federation for Human Rights (Federazione Italiana Diritti Umani – FIDU) | Italian non-profit organization | Promoting and protecting human rights in Italy |

| Antigone Association (Associazione Antigone) | Italian non-profit organization | Civil rights in Italy, with a focus on the penal system |

| International Institute of Humanitarian Law | International legal non-profit | Promoting international humanitarian law in Italy and other countries |

| No Peace Without Justice (Non C’è Pace Senza Giustizia) | Italian non-profit organization | Protecting international human rights |

Useful resources

- Italian Constitution 1948 – English copy of the Constitution of Italy that lays the foundation for the rights of citizens

- Ministry of Justice (Ministero della Giustizia) – the government department responsible for civil liberties in Italy

- Office of the High Commissioner on Human Rights (OHCHR) – UN department working to protect international human rights

- European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) – international convention protecting human rights and freedoms in Europe

- Amnesty International – page on human rights in Italy